On Reading

Introduction

Had I known how much pleasure I would receive from reading novels in later life, I would have read more during my Middle Ages, despite the pressures of home building and career …

I recently read two things that perked my interest. The first was Robert Douglas-Fairhurst’s book ‘Look Closer’, about the importance of close reading. The second was James Marriott’s Substack essay ‘The dawn of the post-literate society’, which warns of dire consequences from the collapse in leisure reading.

Douglas-Fairhurst is the professor of English Literature at Magdalen, Oxford. James Marriott is a Times columnist who I came across in the BBC Radio podcast ‘The Global Story’, as I don’t read the Times.

On Reading

‘Look Closer’ made me think about the importance that reading has had in my own life. ‘The dawn of the post-literate society’ got me thinking about cause and effect.

Reading has been the most consequential activity of my life. Probably more so than my marriage, having children, career choices and the like, hugely important though these have been, partly because of the counterfactual relation between learning to like reading and the life that then followed.

I was a ‘late starter’ at school. Growing up in the Brazil of the 1950’s and 60’s, I didn’t attend school until I was 9 years old. My mother taught me to read and write at home after a fashion, but it was always a struggle. My parents didn’t read stories to me and there weren’t many books in the house. This was the age before TV and before the world became saturated with images. I avoided reading, preferring to spend most of my time sea fishing and swimming.

When I began proper schooling at a boarding school in England I was bottom of the class and remained in the bottom quartile until I was 15.

But something happened at about that age.

I started to enjoy listening to be read to, largely down to an excellent teacher. He spent the last lesson on each Friday afternoon reading to the class. His dramatic way of reading with the use of accents to differentiate the characters drew me into every story. I remember lots of Dickens and Buchan’s Thirty-Nine Steps.

Then I started to enjoy reading on my own. The ‘O’ level exam English Literature texts at the time included Orwell’s Animal Farm, Golding’s Lord of the Flies, Cider with Rosie by Laurie Lee and my then favourite: Salinger’s ‘The Catcher in the Rye’.

I became a committed reader, a novel a week. Forster’s ‘Passage to India’ and ‘Where Angels Fear to Tread’, Orwell, Huxley, and at that time most especially, Evelyn Waugh. I still have these books in my library. I can’t throw books away. It would be like discarding bits of oneself.

Later when we had children, my wife and I would read to them every night. I would always make sure that I left work to arrive home in good time for bed-time stories. As my children became teenagers, they also read frequently and extensively.

Penguin’s marketing spiel about ‘Look Closer’ says the following.

‘This book is for anyone interested in how literature works and makes clear why reading is more relevant than ever in these turbulent times. Funny, illuminating and personal, Look Closer ultimately shows us how great writing can change a person’s life’.

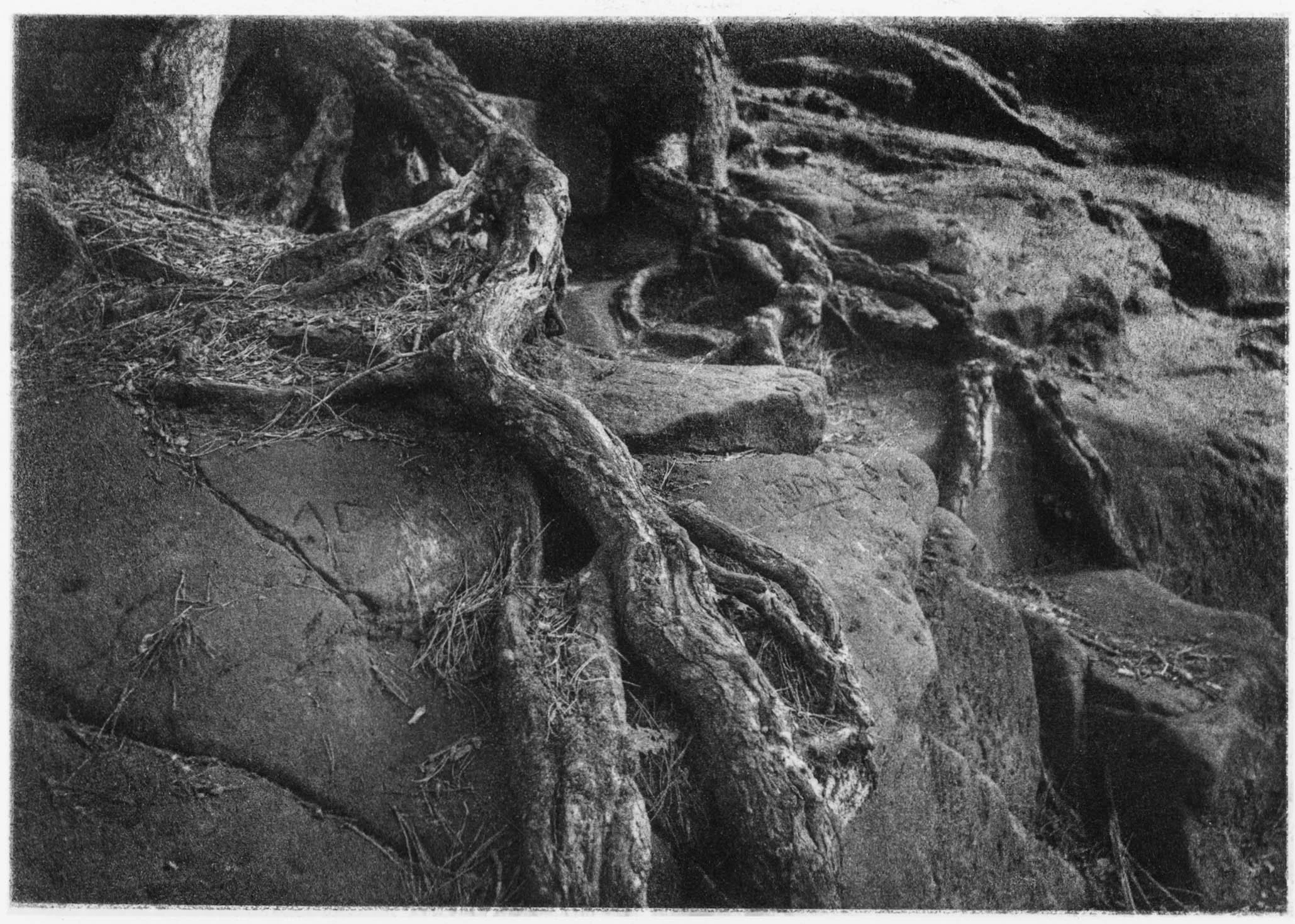

I think that’s a fair characterisation of the book. Learning to like reading certainly changed my life. It planted important roots into my life.

© Tony Cearns - Bromoil l Print - Rhyzomatic Roots

Post literate society?

Marriott's essay (‘The dawn of the post-literate society’) warns that we're entering a "post-literate society" where people, particularly the young, are reading less and spending more time on short videos and social media. He thinks this is dangerous because it's making us less rational and more emotional in how we think and argue.

His main points:

Studies show that reading for fun has dropped dramatically in the US and UK, especially among kids. Reading rates are at record lows.

Smartphones and apps like TikTok have replaced books with quick, fragmented content that trains our brains to be constantly distracted rather than focused.

We are reverting to how people thought before widespread literacy - more emotional reactions, conspiracy theories (he mentions Candace Owens and Russell Brand), and tribal thinking that spreads easily online.

The rational, democratic society we built through print culture is under threat. Complex civilizations need complex thinking tools that reading provides.

Students now struggle with difficult texts and rely on summaries instead of working through original sources. This leads to shallow thinking and less innovation.

Published on his Substack "Cultural Capital" in late 2025, the essay received lots of attention. Many people agreed with his concerns, though some wondered if we're just developing different kinds of intelligence rather than getting dumber. Marriott himself ditched his smartphone for a basic phone so he could read more.

In his essay Marriott relied on the work of Walter Ong (1982, Orality and Literacy, the Technologizing of the Word’. London: Methuen, pp.31, 37-49.) who claimed that reading and writing are essential for developing complex thinking. Now I’m not sure how you distinguish ‘complex’ thinking from simple thinking, but for argument’s sake, let’s just stay with it.

The strongest support for Ong’s view comes from classic 1930s studies by Alexander Luria in rural Uzbekistan. He found that people without literacy tended to think differently from educated people. For example, when given a logic puzzle like ‘All bears in the snowy Far North are white. This place is in the Far North. What colour are the bears?’ - illiterate participants would often refuse to answer, saying they hadn't been there themselves so couldn't know.

Modern research seems to show that:

Learning to read changes brain structure

Children who read early develop stronger cognitive abilities

Reading and critical thinking skills reinforce each other

Written text allows us to review and analyse in ways that spoken words don't

However, recent attempts to repeat Luria's studies haven't found the same results. A 2021 study in India with 161 participants ranging from completely illiterate to highly educated found no significant differences in how they perceived visual illusions - suggesting the cognitive differences might not be as fundamental as once thought.

Critics also point out:

The differences Luria found might simply reflect whether people were willing to cooperate with unfamiliar researchers

Even highly educated adults struggle with formal logic problems

Individual differences matter more than literacy levels

Life experience and cultural context shape thinking as much as literacy does

Today's evidence suggests literacy is better understood as a powerful tool rather than something that fundamentally transforms how humans think. It's particularly helpful for dealing with abstract concepts, following logical structures and analysing information.

But literacy doesn't seem create entirely new cognitive abilities - it enhances and facilitates certain types of thinking that humans perhaps already possess. The divide between oral and literate cultures is better seen as a spectrum with many variations, not a sharp division.

I enjoyed Marriott’s essay, but I I think he has over extrapolated from some quite simple observations.