Shu-Ha-Ri

We don’t have a term in the English language that covers Shu-Ha-Ri (守破離 used in Japan. These are stages on the way to developing a maturity of skill which then enable certain states of mind.

Technical mastery

Acquiring a skill is often equated simply with the learning of a technique. There is a technical side to most endeavours. For example, tying a fly in order to successfully attract wild trout requires a combination of knowledge and dexterity. The knowledge required would include the right size of fly, how it would ‘swim’ or float, the attractants built into the design of the fly, the properties of the various threads and feathers in water, trout behaviour, entomology, the weather, the use of fly-tying tools and so on. The need for dexterity speaks for itself. Finally, less is better than more. A sparseness is required.

A clyde style wetfly from my tying bench

Having tied the fly, further technical mastery is required if the fly is to be presented and fished properly. The choice of casting technique given the wind conditions, keeping a low profile against a sunlit sky, moving slowly and quietly, knowing where the start and end of a swim are, maintaining a drag-free drift for the fly, recognising ‘fishy places’, and so on.

Of course, this is why it takes years to be a good fly angler.

But, one can be adept at fly-fishing, a good technician, but perhaps miss the point of it all.

Shu

The first stage of learning is just to copy the teacher. Here, we try to learn the precision of a form.

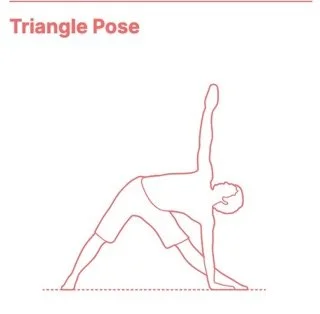

Let’s take the example of Hatha Yoga. At the start of a posture (asana), the teacher will ensure we move sequentially, breathe at the right times, relax and hold into the pose, then unwind from it. Doing this faithfully can take years. Indeed, it never stops. We keep coming back to basics.

Ha

At some point you start to explore the posture, working at its edges whilst being conscious of your own limitations. For example, we might choose to breathe differently, or to engage a muscle in a different way, or to place our minds into an area that doesn’t seem to be engaged. We search for a new balance.

We develop a combination of receptivity and experimentation and start to understand the limitations of compliance in a mechanical way. You start to see why the form exists in the way initially presented and can start adapting them to different situations. You might study with other teachers, explore variations, understand the principles behind the techniques. The form is still there, but you start to apply its principles in different ways.

Ri

We can relate to the Shu-Ha stages since they coincide with our practice in the West. However, the next stage, Ri, is often missing from our western diet. The form flows from your hara without conscious thought. You've internalized the art so completely that you're no longer "doing" techniques - they simply emerge naturally from the situation. Paradoxically, this is where you might appear most simple and natural, yet every gesture carries the full weight of your training. You create freely while honoring the tradition. You understand your limitations precisely because you've found your own way.

The idea here is that attaining a maturity of skill doesn’t stop with technical mastery.

Personal reflection

As a university Biology student back in the 1970’s I saw a poster on a wall about the Japanese Tea Ceremony. It advertised a free demonstration in London by Michael Birch.

Michael Birch was recognized as the sole British Tea Master in the Japanese tea ceremony in the Ura Senke tradition. I don’t know whether Michael Birch is still alive - there is very little on the web about him, except reference to his ‘An Anthology of the Seasonal Feeling in Chanoyu’.

I travelled up to London and, if my memory is correct, the demonstration was at his house.

It had a life-long powerful effect on me that is difficult to describe. The effect stemmed from the tranquillity of the setting, the precision and economy of his movements, the sound of the whisking of the tea and the humming of the kettle over the coals.

Michael Birch wasn’t just giving a demonstration. He was immersed in a flow that enveloped me.

There was something more that came from a short talk given by Michael Birch after his demonstration. It consists in learning to engage with situations and people and objects in such ways that the mind does not exclusively get taken in by them. There is always some reserve, a sense of detachment.

I often think about that demonstration and have often tried to cultivate what I took away from it in other aspects of my life.